This was more common with allied gangs, but from time to time individuals switched to rival groups.

Would such people face threats or even violence? What I found contradicts many longstanding presumptions. In my interviews, I was interested to learn about how often people moved out of gangs or changed their loyalties. Leaving Gangs – Or Switching – Happens Often and Easily Most gang members were part of a close-knit subgroup of four or five people and did not concern themselves with activities beyond that set of associates. Nor did they seem much concerned with those issues.

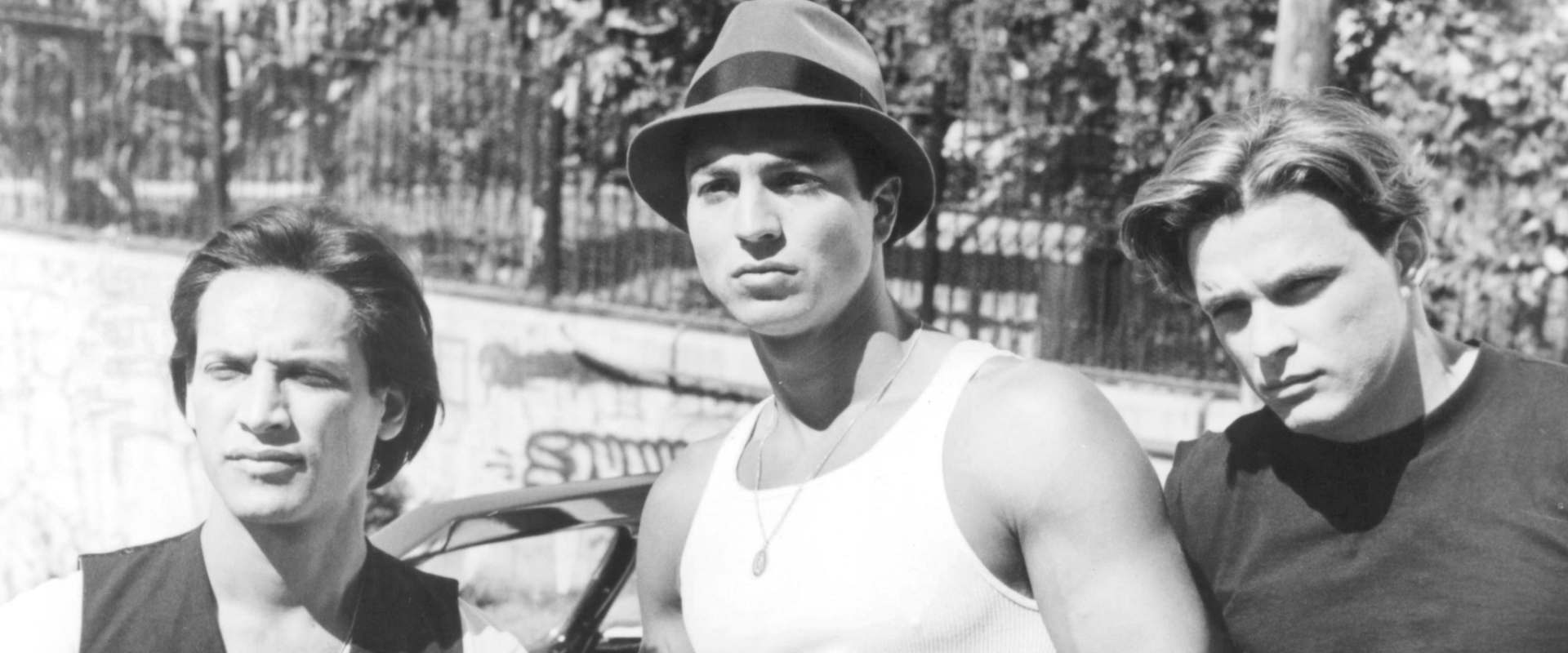

#Blood in blood out gangs verification#

Verification of gang credentials was rejected in favor of a “with us or against us” perspective. Gang members clearly indicated that initiation was not the sole determinant for inclusion in a gang.For example, during a gang fight anyone who supported their side was considered a part of the group. Individual reputations were more important than membership labels in determining a person’s status, and it also seemed to be the case that who was “in” depended on who was actually present during an important event. But in my interviews, gang participants showed little concern about distinguishing mere associates from actual gang members. Traditional ideas about gangs presume that members are always sure who is a member, and who is not. The Fluid Realities of Contemporary Gang Membership In San Antonio, moreover, switching gangs was a fairly common occurrence. From the point of view of participating individuals, gang initiations are not always required, and people often depart from gangs with no dire consequences.

But as has been the case in some previous studies, my results suggest that many of today’s American urban gangs are best understood as unstructured, fluid networks of association.

San Antonio is a good place to look for current trends, because law enforcement agencies classify it as an “emerging gang problem city.” My findings are, of course, subject to further verification by other researchers looking at additional settings. In an exploratory effort to examine contemporary gang behaviors, I completed fourteen in-depth interviews in the city of San Antonio, Texas, with former participants in various gangs called Bloods, Crips, Folks, People, and Surenos. In America today, increased individualism and fluidity characterize gangs as much as other areas of social life and policymaking needs to take account of the new realities. In many other places where non-traditional gang networks have developed since the 1990s, this image of gang structure and membership is more mythical than real. But this conception of gang membership is, at best, based on older studies in cities like Los Angeles and Chicago with long-standing, well-delineated gangs. “Blood in, blood out,” is how the saying goes. Leaving a gang is thought to happen only rarely and be very risky, even fatal for those who try. Joining a gang is considered an intense initiation, perhaps involving the commission of a crime to prove one’s loyalty. Gangs are seen as fixed organizations with clear boundaries. Researchers and law enforcement officials alike often hold a highly stereotyped view of urban gangs and the meaning of gang membership.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)